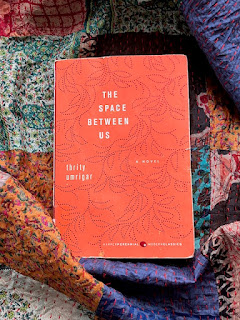

The Space Between Us

Oh, this book, THE SPACE BETWEEN US, by THRITY UMRIGAR. It grabbed and squeezed my heart and triggered all kinds of memories. Bhima and Sera are two women in India, worlds apart in their status in life, one living in the slums, the other in a fancy, spacious upper-middle-class apartment. One an illiterate servant, the other her educated mistress. And yet, they find common ground as they work side by side. They are linked in their shared humanity and suffering, their servitude in their roles as women in a system that firmly divides classes, genders, and status in life. We are drawn into both worlds, the quiet dignity with which Bhima carries herself in her slum dwelling, and Sera’s world of wealth and power but also hopelessness and longing.

*

When I lived in Bahrain, every two years we visited Karachi

for two months during the school summer holidays. My parents were born and

raised there where we had many relatives, and the company my father worked for

in the Gulf, paid our fares (first by ship, then in later years by plane) back

to Pakistan every couple of years.

Life in Karachi was very different from what we were used to

in Bahrain. In our small three-room apartment in Karachi, we had servants who

came daily: the ayah to wash the dishes and sweep the floors, the other girl

who came to clean the bathroom, because even among the servants there was a

distinction of class, and the ayah would not deign to clean toilets. Then there

was the bistiwalla (sp?) who lugged a heavy water sack (was it made of some

kind of animal skin?) up five flights of stairs (no elevator) to fill our water

tank.

We had these servants because it was expected of us.

Everyone in Karachi did, no matter if you were middle-class and lived in a very

modest apartment. Labour was cheap and it provided jobs.

But it was not the norm for us, living in Bahrain, used to doing

our own domestic chores and water flowing constantly from our taps. I sensed my

parents’ discomfort with the stark display of poverty and division of classes. They

tried to mitigate this by slipping a few extra rupees to the servants, and food

to the ayah to take home to her family. My parents’ friends said they were

spoiling things for them, making it worse for them after we returned to Bahrain,

because then the servants would expect more. But we couldn’t shake the

discomfort we felt during those summers every couple of years.

Thrity Umrigar’s book brought all these memories flooding

back to me.

When we walked the route to church or our cousins’ house, we

passed by the slum where our ayah lived. There was a big gate that separated

the area where the servants lived in cramped poverty. Sometimes the gate was

open and I would glance in as we walked by, curious about the squalor that lay

beyond, where there were children like me but not like me. We were worlds

apart.

I was young and impressionable, but also blind to the realities

of the world that lay beyond the big gate. Perhaps this blindness shields us,

protects us, so that we don’t drown in the sorrows and struggles we see in the

lives of others. Because how can we witness it and not be moved by it, not feel

guilty about the comfort of our own lives, which we were born into out of sheer

luck.

But, unfairness and injustices, divisions of classes,

gender-based biases and the chasms between the haves and the have-nots do not

only exist in the India of Umrigar’s books. They exist in the west too. And the

world in her book can be found in our world too.

Comments

Post a Comment